You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

My proposal for one fund with a smoothed return

- Thread starter Colm Fagan

- Start date

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

The following slides should help explain its benefits for an investor.

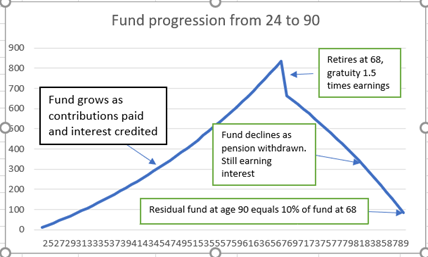

It is like a high-interest deposit account, that an employee has from the date they join the scheme until death. The 'interest rate' on the pension account would be around 4% a year in current market conditions (3.5% after the 0.5% management fee). It will vary up and down but not by much. I suggest contributions of 3% of earnings from employees. Employers will contribute another 3% and the state 1%, so for every €100 contributed by the employee, the account value increases by by €233. That is some incentive to keep contributing.

The overall 'cradle to grave' model is as follows:

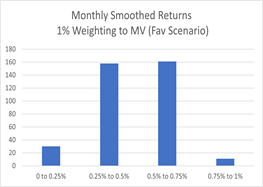

The comparison with a 'lifestyle' approach is as follows, with considerably lower volatility of returns:

Based on experience over the 30 years to end 2019, the volatility of monthly returns would be similar to the right-hand chart below. The left-hand chart shows the distribution of monthly returns for a scheme fully exposed to the equity market. (Monthly returns after charges 0.042% lower than in the chart - i.e. monthly equivalent of 0.5% a year)

To find out more, book for the webinar. It's free! And you don't have to be an actuary. It's from 12:30 to 2:00 on Wednesday. Book here - has to be done in advance:

It is like a high-interest deposit account, that an employee has from the date they join the scheme until death. The 'interest rate' on the pension account would be around 4% a year in current market conditions (3.5% after the 0.5% management fee). It will vary up and down but not by much. I suggest contributions of 3% of earnings from employees. Employers will contribute another 3% and the state 1%, so for every €100 contributed by the employee, the account value increases by by €233. That is some incentive to keep contributing.

The overall 'cradle to grave' model is as follows:

The comparison with a 'lifestyle' approach is as follows, with considerably lower volatility of returns:

‘Lifestyle’ Approach | Smoothed Approach | |

| Total contribution (ratios 3:3:1 for employee, employer, and state) | 14% of earnings | 7% of earnings |

| Gratuity on retirement at age 68 | 1½ times earnings | 1½ times earnings |

| Yearly Pension from 68 to 90: | 50.2% of earnings | 53.8% of earnings |

| Residual Fund at age 90: | 1.34 times earnings | 0.94 times earnings |

Based on experience over the 30 years to end 2019, the volatility of monthly returns would be similar to the right-hand chart below. The left-hand chart shows the distribution of monthly returns for a scheme fully exposed to the equity market. (Monthly returns after charges 0.042% lower than in the chart - i.e. monthly equivalent of 0.5% a year)

To find out more, book for the webinar. It's free! And you don't have to be an actuary. It's from 12:30 to 2:00 on Wednesday. Book here - has to be done in advance:

|

Last edited:

They do help show the investment benefit, that's a lot less volatility! And similar return for a lot less cost!

It's a good start for a one pager, but I think it is missing details on important features from a customers pov (or comparing them to traditianl solution, which might be better) (I realise some of these might depend on the regulartory framework)

From my customer point of view, I'd like to know about the following;

-Ability to stop/start/increase/decrease contributions (I think this is same as normal pension)

-lump sum contributions?

-transferring (if such a thing would exist)

-Can I early retire and access the fund at 50 years old (which some pensions/prsa can)

-Pre retirment access to their money (You implied this could be supported)

-Post-retirment access to your money (I think it is more restrictive? but should suit most people who simply want to live/have an income from their pension)

(I realise most of these are probably detailed in the paper, and some were discussed in some past threads, but I still haven't read the paper. I think anyone 'voting' for this, will be looking at the benefits for the state, and the benefit for the individuals, so it seems important to me to have a succinct one pager/marketing material addressing the investor features)

It's a good start for a one pager, but I think it is missing details on important features from a customers pov (or comparing them to traditianl solution, which might be better) (I realise some of these might depend on the regulartory framework)

From my customer point of view, I'd like to know about the following;

-Ability to stop/start/increase/decrease contributions (I think this is same as normal pension)

-lump sum contributions?

-transferring (if such a thing would exist)

-Can I early retire and access the fund at 50 years old (which some pensions/prsa can)

-Pre retirment access to their money (You implied this could be supported)

-Post-retirment access to your money (I think it is more restrictive? but should suit most people who simply want to live/have an income from their pension)

(I realise most of these are probably detailed in the paper, and some were discussed in some past threads, but I still haven't read the paper. I think anyone 'voting' for this, will be looking at the benefits for the state, and the benefit for the individuals, so it seems important to me to have a succinct one pager/marketing material addressing the investor features)

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

Hi @SPC100

Can't really be compared with a traditional pension, as approach would not work in a conventional structure. It has to be in an AE style structure.

Ability to vary contributions? Remember that this is designed as a type of employer-sponsored scheme, which will be rolled out in time to our local tyre repair shop, bakery, restaurant. Employees contribute 3% of earnings, employer pays the same, and state pays 1%. Anyone can stop contributing (or decide not to join in the first place) but they need their head examined if they do. For every €100 they contribute, €233 is added to their account. As far as I know with AE generally, you either contribute the 3% (or whatever) or don't contribute at all. No possibility of paying more by way of AVC's, etc. These are accommodated under non-AE arrangements. Remember too that earnings over €70k not covered.

Transfers? Under my proposal, there would be no transfers. You can stop contributing and start a plan with a commercial provider, but your accumulated funds remain in the scheme. They get exactly the same return as everyone else and there are no policy fees, so you don't lose out. No transfers is an absolutely essential element of the smoothing approach. It just won't work with transfers.

Can I retire early? As I said, it's just like a deposit account, so there's no technical problem with 'retiring' early and starting to withdraw, but I think that you would need to have genuinely retired. Anyway, seems stupid to 'retire' if you're still working, as you miss out on the other €133 mentioned above.

Pre-retirement access? As I wrote, I don't have a problem with the sort of access for house purchase that Brendan suggested earlier. Personally, I'm not a fan of it, but for quite different reasons.

Post-retirement access? As I wrote, I'm suggesting lower and upper limits of 3% and 8% of account value per year. Not written in stone. The main point is that people cannot keep changing the amount withdrawn just because smoothed values are above or below market values. I don't see any problem with rules allowing variations for part-time work (for instance), e.g., working part-time, they decide they'll only take 2% a year, but want to increase it to 6% once they stop the part-time work. All that's needed to avoid the anti-selection that's worrying me is (say) 3 months' notice of intention to change the amount of the withdrawal. (We're getting into the innards here).

Can't really be compared with a traditional pension, as approach would not work in a conventional structure. It has to be in an AE style structure.

Ability to vary contributions? Remember that this is designed as a type of employer-sponsored scheme, which will be rolled out in time to our local tyre repair shop, bakery, restaurant. Employees contribute 3% of earnings, employer pays the same, and state pays 1%. Anyone can stop contributing (or decide not to join in the first place) but they need their head examined if they do. For every €100 they contribute, €233 is added to their account. As far as I know with AE generally, you either contribute the 3% (or whatever) or don't contribute at all. No possibility of paying more by way of AVC's, etc. These are accommodated under non-AE arrangements. Remember too that earnings over €70k not covered.

Transfers? Under my proposal, there would be no transfers. You can stop contributing and start a plan with a commercial provider, but your accumulated funds remain in the scheme. They get exactly the same return as everyone else and there are no policy fees, so you don't lose out. No transfers is an absolutely essential element of the smoothing approach. It just won't work with transfers.

Can I retire early? As I said, it's just like a deposit account, so there's no technical problem with 'retiring' early and starting to withdraw, but I think that you would need to have genuinely retired. Anyway, seems stupid to 'retire' if you're still working, as you miss out on the other €133 mentioned above.

Pre-retirement access? As I wrote, I don't have a problem with the sort of access for house purchase that Brendan suggested earlier. Personally, I'm not a fan of it, but for quite different reasons.

Post-retirement access? As I wrote, I'm suggesting lower and upper limits of 3% and 8% of account value per year. Not written in stone. The main point is that people cannot keep changing the amount withdrawn just because smoothed values are above or below market values. I don't see any problem with rules allowing variations for part-time work (for instance), e.g., working part-time, they decide they'll only take 2% a year, but want to increase it to 6% once they stop the part-time work. All that's needed to avoid the anti-selection that's worrying me is (say) 3 months' notice of intention to change the amount of the withdrawal. (We're getting into the innards here).

Brendan Burgess

Founder

- Messages

- 55,194

This webinar takes place tomorrow, Wednesday, from 12.30 to 2 pm.

You must register to attend.

Brendan

You must register to attend.

Brendan

It seems one of the big risks identified, especially for the future, when the fund is mature and may (will?) have more outflows than inflows, is if the smoothed value remains above the market value for an extended period of time. (this appeared to be the case in the 2 failures you identified in the talk). In particular if SV was ever > 233 when MV is 100, it would appear to not be rational for people to continue to invest, which could accerlate fund flow issues.

what patterns of market values can realistically result in elongated periods of time with SV above MV?

Have you considered complicating your smoothing function with an emergency hatch to reduce this risk? e.g. accelerate fater to the market value, if SV has been above MV by >p percent for n months.

At some point we have to accept the reality of market prices.

what patterns of market values can realistically result in elongated periods of time with SV above MV?

Have you considered complicating your smoothing function with an emergency hatch to reduce this risk? e.g. accelerate fater to the market value, if SV has been above MV by >p percent for n months.

At some point we have to accept the reality of market prices.

Duke of Marmalade

Registered User

- Messages

- 4,704

Good points SPC100. Some actuaries who support the thrust of the proposals feel that hard wiring the formula could be too rigid and that there should be scope to review it if circumstances change significantly. This point was made by the opener to the discussion, Seamus Creedon. The problem with making it even in principle open to review is that there would be an impetus for political pressures to do so if SV and MV get significantly out of kilter. Any review mechanism would need to have very clear manners put on it.It seems one of the big risks identified, especially for the future, when the fund is mature and may (will?) have more outflows than inflows, is if the smoothed value remains above the market value for an extended period of time. (this appeared to be the case in the 2 failures you identified in the talk). In particular if SV was ever > 233 when MV is 100, it would appear to not be rational for people to continue to invest, which could accerlate fund flow issues.

what patterns of market values can realistically result in elongated periods of time with SV above MV?

Have you considered complicating your smoothing function with an emergency hatch to reduce this risk? e.g. accelerate fater to the market value, if SV has been above MV by >p percent for n months.

At some point we have to accept the reality of market prices.

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

First of all, thanks for your constructive engagement, your good understanding of what I'm proposing, and your good questions.At some point we have to accept the reality of market prices.

There has been some misunderstanding of what I'm saying about market values and smoothed values. In particular, some in officialdom think that I am suggesting that there will be a 'reversion to mean', i.e. that market values will revert to some sort of smoothed mean over time. No, I am saying exactly the opposite. The smoothing formula is designed to gradually bring smoothed values towards market values, not to bring market values towards smoothed values.

I also accept the ultimate supremacy of the market, that all asset purchases and sales take place at market values. That is why I gave your post a 'like'. Members transact with the scheme at smoothed values on the clear understanding that they can only transact at those values for agreed amounts, i.e. regular contribution when buying, scheduled withdrawals (gratuity on retirement, regular pension payment or death benefit) when selling. It is precisely because I accept the supremacy of the market that I am setting those rules. Members are not allowed to transact with the scheme otherwise (except the possibility I entertained of Brendan's suggestion of withdrawing to pay a deposit for their first house).

I agree with your identification of the risks. I also have a lot of sympathy for your suggested solution. As @Duke of Marmalade writes, you are far from alone. If I were a prospective 'customer' of the scheme, however, I would be worried about joining a club where the rules could be changed if they weren't giving the right results. That is the main reason I am holding back from agreeing with you. I also believe that time is a great healer and a great solver of problems. We are all agreed that the problem we are discussing will not rear its head until cash flows turn negative. The model says that won't happen for 50 years. As I write in the paper, cash flows are likely to remain positive for even longer. I also believe that the buffer account will build up significantly over time. I am reasonably confident that the projection of 0.2% a year going to the buffer account from year 20 is an underestimate, that total costs will work out at less than 0.3% in the longer run, thus allowing more than 0.2% to go to the buffer account. The buffer account will also help a great deal when cash flows turn negative.It seems one of the big risks identified, especially for the future, when the fund is mature and may (will?) have more outflows than inflows, is if the smoothed value remains above the market value for an extended period of time. (this appeared to be the case in the 2 failures you identified in the talk). In particular if SV was ever > 233 when MV is 100, it would appear to not be rational for people to continue to invest, which could accerlate fund flow issues.

How about something in-between? Suppose we say that the rules as set out at the start will apply for the first (say) 25 years and that they will then be subjected to an independent review, to see how they can be improved?

Last edited:

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

It depends on when market values fall. If they fall sharply in the early years, when cash is flooding in, then the smoothing formula can take nearly anything that is thrown at it. For example, in the 'adverse scenario' of Section 8 (a repeat of Japan from the start of 1990) market values fall 55% in the first three years, yet smoothed values are below market values at a dozen month ends in the first four years (see Section 12.11).what patterns of market values can realistically result in elongated periods of time with SV above MV?

It's a different story if there is a sharp fall when the fund is mature and cash flows have turned negative (projected from year 50). The paper recognises that the circumstances could be very different then. That is why it is proposed to establish a buffer account (from around year 20) to cover that eventuality. Another possibility is that, at the 25-year review (suggested at the end of my previous post), the trustees could increase the weighting for current market value in the smoothing formula, to reduce the risk of smoothed values falling too far below market values in bad times. By that stage, the scheme will have 25 years under its belt and people will have got very familiar with its operations. That could make them more ready to accept slightly more volatile returns (although I doubt it. We all hate losing money:. I've been losing money - and making the occasional few bob - on investments for decades at this stage, and losing still pains me).

This seems on the face of it to be an elegant attempt at a reworking of the old actuarial favourite a “with profits” fundI nearly wept this morning, hearing Regina Doherty on RTE with Rachel English, going over old ground of people having to decide whether they want to be low, medium or high risk; what happens if markets tumble on the day people retire; the carousel (probably one of the most ridiculous concepts ever devised); etc. I'm now absolutely convinced that the only way to avoid making a complete dog's dinner of AE is to adopt the smoothed, equity-based approach I've been advocating. A straightforward explanation can be found here. Additional papers and explanations can be found at http://www.colmfagan.ie/pensions.php

Unfortunately, it's proving difficult to get government, even my own profession, engaged. The prevailing view is that the proposals are too radical: "What you're proposing, Colm, hasn't been done anywhere else in the world; we don't want to be the first to try them out."

Smoothed investment returns offer the appearance of a steady “bank interest” like return from an inherently volatile underlying capital asset like equites.

Here the insurance company pretended to investors that equites don’t fluctuate and added a smoothed annual bonus to their policy. Once added these reversionary bonuses cannot be taken away. Investors also anticipated a terminal bonus on maturity.

The problems with these policies are well documented. And in the extreme, Guaranteed annuity rates on pensions destroyed the once venerable Equitable Life.

Poorly understood “market value adjustments” and the need to pay zero bonuses and move the underlying assets into bonds following the tech bubble in the early naughties passed these products into what many of us hoped would be the history books.

I was simply amazed that they were still being flogged by brokers when I arrived in Ireland in 2008.

Another example of a similar structure from an investor’s perspective is a defined benefit pension which protects the members pension at the expense of costs being born by the employer.

There was a joke in the City of London for many years that BA was a pension company that flew aeroplanes as hobby because the the hole in their defined benefit pension scheme.

In both these examples, the cost of meeting the contractual commitments were too high to bear from either a prudent regulatory capital perspective for the life insurance industry or in the corporate world.

Many States around the world also have a history of offering a universal retirement saving scheme in the form of social security and state pensions.

Here again experience has shown that the cost of providing a universal retirement income, albeit on an unfunded basis, is too high and many countries have sought to address the increased costs from rising life expectancies by pushing back the retirement age.

We saw in France only recently how attempts to manage these costs are sometimes met by the public.

In Ireland, of course, the state also has another unfunded liability in the form of the public sector pension liability which I was reliably told many years ago was already standing at twice the liability arising from the bail out of the banks in the financial crisis.

Under the conditions that the Life Cos, the Corporate Sector and States generally have all struggled and, to a greater or lesser extent failed, to underwrite the increasing costs being incurred by an aging population i’m hardly surprised it’s a difficult sell to expect a politician to sign up to underwriting a guarantee that an entire countries retirement savings could be linked to global capital markets and the risk of a collapse underwritten by the State.

How likely is a very significant shock to capital markets? If stock returns were normally distributed a 40% decline as we saw in the financial crisis should be expected as normal in capital markets and should occur on average around 2.5% of the time or one year in 40.

But stock returns aren’t even normally distributed and “fat tails” are a feature of capital markets.

The worst year on record for the US market was in the early 1930s during the Great Depression when the US market dropped by around two thirds.

Rare events whilst improbable are not impossible and failing to account for extreme market conditions blew up both LTCM and Lehmans.

“Consider the stock market collapse during the Russian bond default of August 1998. On 4 August the Dow fell 3.5% and, three weeks later, as the news worsened, stock fell again, by 4.4%, and then again, on the 31 August, by 6.8%.

Theory would estimate the odds of that final 31 August collapse at one in 20 million – an event which, were you to trade daily for almost 100,000 years, you would not expect to see even once. The odds of getting three such declines in the same month were about one in 500 billion.

A year earlier, the Dow had fallen 7.7% in one day (probability: one in 50 billion). In July, 2002, the index recorded three steep falls within seven trading days (probability: one in four trillion). And on 19 October 1987, the worst day of trading in at least a century, the index fell 29.2%. The probability of that happening, according to orthodox financial theory, was less than one in 10 to the 50, odds so small they have no meaning, and are beyond the scale of nature.

You could search for powers of ten from the smallest sub-atomic particle to the breadth of the observable universe and still never meet such a number.”

Recently the philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan has attacked the use of Gaussian (normal bell curve) mathematics as the foundation of finance.

Taleb is a fan of Mandelbrot, whose mathematics account for fat tails. He argues that the bell curve doesn't reflect reality and this means stochastic models for market returns are more complicated.

In 1963, Mandelbrot modelled cotton prices with a Lévy stable process, and his finding was later supported by Eugene Fama in 1965.

The S&P 500 has suffered 10 monthly returns worse than three standard deviations below its mean.

The log-stable model does a better job of capturing the S&P 500’s extremes than the lognormal model, but its tails are too fat.

As I have shown, seeking to mix capital guarantees of any sort and inherently volatile capital assets has a history of bad outcomes.

However, whilst the short-term distribution of capital market returns can sink anyone trying to underwrite a guarantee, for the long term passive investor we can choose to ignore the short term noise.

“We agree that Mandelbrot is right. As we can see when looking at the daily market returns, the distribution is fat-tailed relative to the normal distribution.

In other words, extreme returns occur much more often than would be expected if returns were normal.

However most of what we do in terms of portfolio theory and models of risk and expected return works for Mandelbrot's stable distribution class, as well as for the normal distribution.

Our conclusion is that for long-term passive investors, the short term

distribution doesn’t matter beyond being aware that outlier returns are more common than would be expected if return distributions were normal.”

Eugene F Fama

In other words smoothing of investment returns isn’t required for investment reasons and adds unnecessary complexity. It’s required for emotional and psychological reasons to address our innate tendency towards loss aversion. And that leads us on to the field of behavioural finance.

Thaler and others in the behavioural finance world have shown that auto enrolment works mainly due to the nudge effect of having to opt out rather than opt in.

The lions share of the “issue” here is the lack of universal coverage in private pension provision in excess of social security. Many people are not saving for their retirement and have little more than the basic state pension to see them through.

This part of the puzzle isn’t an investment problem at all but rather a question of how a civilised society should provide for people in old age.

Governments could simply increase PRSI. (This article supports this line of reasoning.https://www.irishtimes.com/politics/2023/05/10/windfall-tax-receipts-will-not-be-enough-to-cover-cost-of-ageing-population/) and increase the basic state pension but that is a vote losing increase in tax which would benefit everyone equally and some need the additional pension more than others.

“Making” (they can opt out) people save for their retirement is a form of tax by another name.

Even if the returns on these saving are only equal to inflation that is still slightly better from the perspective of the both the state and the investor than an unfunded liability.

Published work on this subject can be found by Nobel Prize winner Bob Merton who concluded that an intermediate term inflation linked bond would do the job pretty well.

I’ll end with a philosophical question: why isn’t the underlying investment for auto enrolment directly invested by NTMA?

Contributions, or at least some of the contributions, could be used for publicly funded infrastructure projects. And, this doesn’t have to mean much lower returns for investors.

I’m personally getting 10%pa in my pension investing in residential social housing projects in the U.K. for example.

If people were shown how their contributions were being invested to address issues here in Ireland like homelessness, climate change, poor provision of services to people with disabilities or whatever social or environmental issues you might care to list rather than further boosting the profits of US multinationals they might be more willing to get behind it.

But as I sort of alluded to earlier isn’t that also why we pay taxes?

Last edited:

I’m personally getting 10%pa in my pension investing in residential social housing projects in the U.K. for example.

I'll leave it to others to comment on the post more broadly.

Is this 10% your anticipated future return (over, say, the next few years) or what has been achieved?

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

Hi @Marc, you're right that the smoothed approach to auto-enrolment and with profits share the same objective of allowing savers to enjoy the benefits of equity investment while protecting them from the associated volatility. There are some key differences, however, which mean that the smoothed approach to AE keeps the good parts of with-profits and ditches the bad parts.This seems on the face of it to be an elegant attempt at a reworking of the old actuarial favourite a “with profits” fund

Smoothed investment returns offer the appearance of a steady “bank interest” like return from an inherently volatile underlying capital asset like equites.

.... The problems with these policies are well documented. And in the extreme, Guaranteed annuity rates on pensions destroyed the once venerable Equitable Life.

Poorly understood “market value adjustments” and the need to pay zero bonuses and move the underlying assets into bonds following the tech bubble in the early noughties passed these products into what many of us hoped would be the history books.

1. Unlike with-profits, the trustees/directors/managers (and most of all, the actuary!) have no discretion on ‘interest rates’ credited to members’ accounts. They are determined by a formula that is tamper-proof.

2. The directors/trustees have no discretion on asset allocation: 100% is invested in ‘equities’, always. With-profit companies have been accused of acting against policyholders’ long-term interests by moving assets pro-cyclically from equities to bonds when markets fell, at the risk of exacerbating market falls. There is no such risk with the smoothed approach to AE.

3. There is no need for an ‘estate’, with the associated need to hold back returns credited to members in the early years. A ‘buffer account’ will be needed by the time cash flows eventually turn negative, which is expected sometime after year 30, to pay the excess (if any) of smoothed value over market value for net exits. Similarly, the buffer account will be credited whenever market value exceeds smoothed value for net exits from when cash flows turn negative. The buffer account will be funded from margins in the management charge, which will emerge from around year 15. Projections indicate that the buffer account will be more than adequately funded by the time cash flows turn negative.

4. There are no guarantees, so they won't cause any problems. Members will get the average smoothed return on the fund, where smoothing is done over a long period. Over the last 30 years at least, probably much longer, smoothed returns, determined in accordance with the proposed formula, would have been positive every month. There is the possibility, of course, of the occasional negative return in future; however, the chances are extremely small. Even if there is a negative return, it will be for a very small percentage, and for a very short time.

5. Members will get the full account value plus interest at retirement (a retirement gratuity) or during retirement (a regular pension) or on death. There will be no "market value adjustments".

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

Hi @Marc

Getting back to you on some of your other criticisms of my proposed smoothed approach to Auto-Enrolment.

You outshone even yourself with your references!

My point is that, stripped to its essentials, AE is one big national wealth fund. It will enjoy positive cash flows for decades - at least 30 years - so the key objective is to invest net income (contributions less benefits) to earn the highest possible sustainable return over a very long investment horizon. What happens to market values in the short-term is of little concern, other than that occasional sharp increases in market values mean buying more expensively while occasional sharp drops mean getting in on the cheap. Share prices can follow all the non-Gaussian, non-stable, Mandelbrot, Levy, Fama models that were ever invented, but all the gyrations in the world don't matter a whit to scheme members - PROVIDED THAT we can devise a system for transferring assets from retired workers who are taking a regular pension from the scheme to continuing and joining members in a manner that is fair - and seen to be fair - to all, and that eliminates the mad Mandelbrot/ Levy/ non-Gaussian/ unstable short-term changes in market values, while allowing the scheme's managers/ trustees/ directors to do what they should be doing, i.e., focusing on making value-adding long-term investments, without worrying about the short-term.

That's what I think I've achieved with my proposal , while also recognising the ultimate primacy of market values when/if the scheme ultimately declines and has negative cash flows.

Of course, I recognise that my approach can only work for AE. Outside AE, it will not be possible to mandate that contributors must join and leave at smoothed rather than market values.

Getting back to you on some of your other criticisms of my proposed smoothed approach to Auto-Enrolment.

You outshone even yourself with your references!

And all in a single post!! I am impressed! But what does it all mean?philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb .... Gaussian (normal bell curve) ....Mandelbrot .... bell curve ... stochastic models .... Lévy stable process .... supported by Eugene Fama log-stable model .. better than .. lognormal .. tails too fat . portfolio theory ... Mandelbrot's stable distribution class ... Thaler .. behavioural finance ... Nobel Prize winner Bob Merton

My point is that, stripped to its essentials, AE is one big national wealth fund. It will enjoy positive cash flows for decades - at least 30 years - so the key objective is to invest net income (contributions less benefits) to earn the highest possible sustainable return over a very long investment horizon. What happens to market values in the short-term is of little concern, other than that occasional sharp increases in market values mean buying more expensively while occasional sharp drops mean getting in on the cheap. Share prices can follow all the non-Gaussian, non-stable, Mandelbrot, Levy, Fama models that were ever invented, but all the gyrations in the world don't matter a whit to scheme members - PROVIDED THAT we can devise a system for transferring assets from retired workers who are taking a regular pension from the scheme to continuing and joining members in a manner that is fair - and seen to be fair - to all, and that eliminates the mad Mandelbrot/ Levy/ non-Gaussian/ unstable short-term changes in market values, while allowing the scheme's managers/ trustees/ directors to do what they should be doing, i.e., focusing on making value-adding long-term investments, without worrying about the short-term.

That's what I think I've achieved with my proposal , while also recognising the ultimate primacy of market values when/if the scheme ultimately declines and has negative cash flows.

Of course, I recognise that my approach can only work for AE. Outside AE, it will not be possible to mandate that contributors must join and leave at smoothed rather than market values.

Last edited:

Duke of Marmalade

Registered User

- Messages

- 4,704

Wow!! Lots in there, but I will focus in this post on the theme of the inappropriateness of the Normal model. I agree that it is absolutely crazy to use the Normal model for say daily price movements, though I understand that some quants did just that and it was a contributory factor in the GFC.This seems on the face of it to be an elegant attempt at a reworking of the old actuarial favourite a “with profits” fund

Smoothed investment returns offer the appearance of a steady “bank interest” like return from an inherently volatile underlying capital asset like equites.

Here the insurance company pretended to investors that equites don’t fluctuate and added a smoothed annual bonus to their policy. Once added these reversionary bonuses cannot be taken away. Investors also anticipated a terminal bonus on maturity.

The problems with these policies are well documented. And in the extreme, Guaranteed annuity rates on pensions destroyed the once venerable Equitable Life.

Poorly understood “market value adjustments” and the need to pay zero bonuses and move the underlying assets into bonds following the tech bubble in the early naughties passed these products into what many of us hoped would be the history books.

I was simply amazed that they were still being flogged by brokers when I arrived in Ireland in 2008.

Another example of a similar structure from an investor’s perspective is a defined benefit pension which protects the members pension at the expense of costs being born by the employer.

There was a joke in the City of London for many years that BA was a pension company that flew aeroplanes as hobby because the the hole in their defined benefit pension scheme.

In both these examples, the cost of meeting the contractual commitments were too high to bear from either a prudent regulatory capital perspective for the life insurance industry or in the corporate world.

Many States around the world also have a history of offering a universal retirement saving scheme in the form of social security and state pensions.

Here again experience has shown that the cost of providing a universal retirement income, albeit on an unfunded basis, is too high and many countries have sought to address the increased costs from rising life expectancies by pushing back the retirement age.

We saw in France only recently how attempts to manage these costs are sometimes met by the public.

In Ireland, of course, the state also has another unfunded liability in the form of the public sector pension liability which I was reliably told many years ago was already standing at twice the liability arising from the bail out of the banks in the financial crisis.

Under the conditions that the Life Cos, the Corporate Sector and States generally have all struggled and, to a greater or lesser extent failed, to underwrite the increasing costs being incurred by an aging population i’m hardly surprised it’s a difficult sell to expect a politician to sign up to underwriting a guarantee that an entire countries retirement savings could be linked to global capital markets and the risk of a collapse underwritten by the State.

How likely is a very significant shock to capital markets? If stock returns were normally distributed a 40% decline as we saw in the financial crisis should be expected as normal in capital markets and should occur on average around 2.5% of the time or one year in 40.

But stock returns aren’t even normally distributed and “fat tails” are a feature of capital markets.

The worst year on record for the US market was in the early 1930s during the Great Depression when the US market dropped by around two thirds.

Rare events whilst improbable are not impossible and failing to account for extreme market conditions blew up both LTCM and Lehmans.

“Consider the stock market collapse during the Russian bond default of August 1998. On 4 August the Dow fell 3.5% and, three weeks later, as the news worsened, stock fell again, by 4.4%, and then again, on the 31 August, by 6.8%.

Theory would estimate the odds of that final 31 August collapse at one in 20 million – an event which, were you to trade daily for almost 100,000 years, you would not expect to see even once. The odds of getting three such declines in the same month were about one in 500 billion.

A year earlier, the Dow had fallen 7.7% in one day (probability: one in 50 billion). In July, 2002, the index recorded three steep falls within seven trading days (probability: one in four trillion). And on 19 October 1987, the worst day of trading in at least a century, the index fell 29.2%. The probability of that happening, according to orthodox financial theory, was less than one in 10 to the 50, odds so small they have no meaning, and are beyond the scale of nature.

You could search for powers of ten from the smallest sub-atomic particle to the breadth of the observable universe and still never meet such a number.”

Recently the philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan has attacked the use of Gaussian (normal bell curve) mathematics as the foundation of finance.

Taleb is a fan of Mandelbrot, whose mathematics account for fat tails. He argues that the bell curve doesn't reflect reality and this means stochastic models for market returns are more complicated.

In 1963, Mandelbrot modelled cotton prices with a Lévy stable process, and his finding was later supported by Eugene Fama in 1965.

The S&P 500 has suffered 10 monthly returns worse than three standard deviations below its mean.

The log-stable model does a better job of capturing the S&P 500’s extremes than the lognormal model, but its tails are too fat.

As I have shown, seeking to mix capital guarantees of any sort and inherently volatile capital assets has a history of bad outcomes.

However, whilst the short-term distribution of capital market returns can sink anyone trying to underwrite a guarantee, for the long term passive investor we can choose to ignore the short term noise.

“We agree that Mandelbrot is right. As we can see when looking at the daily market returns, the distribution is fat-tailed relative to the normal distribution.

In other words, extreme returns occur much more often than would be expected if returns were normal.

However most of what we do in terms of portfolio theory and models of risk and expected return works for Mandelbrot's stable distribution class, as well as for the normal distribution.

Our conclusion is that for long-term passive investors, the short term

distribution doesn’t matter beyond being aware that outlier returns are more common than would be expected if return distributions were normal.”

Eugene F Fama

In other words smoothing of investment returns isn’t required for investment reasons and adds unnecessary complexity. It’s required for emotional and psychological reasons to address our innate tendency towards loss aversion. And that leads us on to the field of behavioural finance.

Thaler and others in the behavioural finance world have shown that auto enrolment works mainly due to the nudge effect of having to opt out rather than opt in.

The lions share of the “issue” here is the lack of universal coverage in private pension provision in excess of social security. Many people are not saving for their retirement and have little more than the basic state pension to see them through.

This part of the puzzle isn’t an investment problem at all but rather a question of how a civilised society should provide for people in old age.

Governments could simply increase PRSI. (This article supports this line of reasoning.https://www.irishtimes.com/politics/2023/05/10/windfall-tax-receipts-will-not-be-enough-to-cover-cost-of-ageing-population/) and increase the basic state pension but that is a vote losing increase in tax which would benefit everyone equally and some need the additional pension more than others.

“Making” (they can opt out) people save for their retirement is a form of tax by another name.

Even if the returns on these saving are only equal to inflation that is still slightly better from the perspective of the both the state and the investor than an unfunded liability.

Published work on this subject can be found by Nobel Prize winner Bob Merton who concluded that an intermediate term inflation linked bond would do the job pretty well.

I’ll end with a philosophical question: why isn’t the underlying investment for auto enrolment directly invested by NTMA?

Contributions, or at least some of the contributions, could be used for publicly funded infrastructure projects. And, this doesn’t have to mean much lower returns for investors.

I’m personally getting 10%pa in my pension investing in residential social housing projects in the U.K. for example.

If people were shown how their contributions were being invested to address issues here in Ireland like homelessness, climate change, poor provision of services to people with disabilities or whatever social or environmental issues you might care to list rather than further boosting the profits of US multinationals they might be more willing to get behind it.

But as I sort of alluded to earlier isn’t that also why we pay taxes?

My approach is that the model for short term price movements would be extremely complex, impossible to calibrate and mathematically totally intractable. Just like the movement of a grain of pollen in water being buffeted by molecules. But as Robert Brown noticed, if we track the movement of the pollen after many, many such buffetings its statistical distribution tends to Normal or Brownian as it has been called in his honour. This has also been proved mathematically as the Central Limit Theorem which states that no matter how bizarre the distribution of the individual steps, if they are independent in a Random Walk then as the number of these steps increases we approach a Normal distribution.

These days stockmarket movements are almost every second and independence is probably substantially present after maybe a few weeks, so that after a year, say, the distribution should approach the (log)normal or Geometric Brownian as stated by the CLT.

Leaving the mathematical hubris aside, I will ponder the more relevant points of your post in terms of what it means for Colm's proposal.

Last edited:

Duke of Marmalade

Registered User

- Messages

- 4,704

@Marc

I am not sure what all the mathematical hubris was about in the context of this topic. Are you suggesting that there are non-negligible possibilities that Colm's proposal will crash and burn? Contradicts somewhat your conviction that, long term, equities are yer only man. In any event even as it stands AE funds will be almost entirely in equities for about 30 years and it is only after that, when retirements become significant, that Colm's proposal sustains the 100% commitment to growth assets.

Your comparison of Colm's proposal with With Profits is about as apposite as comparing a modern jet airliner with that guy Icarus (see I can name drop). They share in common the desire to smooth the allocation of equity returns, as the latter shared a belief that humans could fly. That's where the comparison ends as Colm explained in post #72.

These are precisely Colm's arguments. Colm sees pension provision as a whole life investment where the "short term distribution doesn't matter". But he does put more store on the behavioural dimension that you refer to. He sees lifestyling as being a slave to this behaviour. One approach, which it seems you are advocating is that people just let it run and ignore the short term volatility. Colm's approach takes the behavioural aspect somewhat more seriously and actually provides concrete solace to those who would not be convinced by your argument that it will all be alright on the night. There is also an element of substance rather than mere optics in Colm's suggestion as it would involve an element of cross cohort volatility pooling. Your post also refers to the complexity of Colm's proposal. I think you are misunderstanding his proposal. He envisages, say quarterly, declarations of "interest" applicable to all accounts rather than daily unit pricing. He argues that it could be implemented even quicker than what is currently proposed.Marc #70 said:However, whilst the short-term distribution of capital market returns can sink anyone trying to underwrite a guarantee, for the long term passive investor we can choose to ignore the short term noise.

...

Our conclusion is that for long-term passive investors, the short term

distribution doesn’t matter beyond being aware that outlier returns are more common than would be expected if return distributions were normal.

In other words smoothing of investment returns isn’t required for investment reasons and adds unnecessary complexity. It’s required for emotional and psychological reasons to address our innate tendency towards loss aversion. And that leads us on to the field of behavioural finance.

I am not sure what all the mathematical hubris was about in the context of this topic. Are you suggesting that there are non-negligible possibilities that Colm's proposal will crash and burn? Contradicts somewhat your conviction that, long term, equities are yer only man. In any event even as it stands AE funds will be almost entirely in equities for about 30 years and it is only after that, when retirements become significant, that Colm's proposal sustains the 100% commitment to growth assets.

Your comparison of Colm's proposal with With Profits is about as apposite as comparing a modern jet airliner with that guy Icarus (see I can name drop). They share in common the desire to smooth the allocation of equity returns, as the latter shared a belief that humans could fly. That's where the comparison ends as Colm explained in post #72.

Last edited:

Colm Fagan

Registered User

- Messages

- 763

AAM readers may be interested in the following, which I posted on LinkedIn this morning:

Auto-enrolment is on the agenda for IAPF's summer conference tomorrow. CEO Jerry Moriarty tells me that there are more pressing matters to discuss than my proposal for a smoothed equity approach to investment. How stupid of me to think that saving €1.4 billion a year was more important than deciding how best to offer workers a choice of investments.

I'm disappointed not to have the opportunity to explain how the smoothed equity approach delivers more than 50% better value than government's proposals, nor how it eliminates the risk of sharp falls in members' account values, to such an extent that AE accounts can be administered like high interest savings accounts. I'm also disappointed not be be able to explain how workers keep the same accounts post-retirement as they had pre-retirement, just drawing from them rather than adding to them. Surely, IAPF members would be delighted to learn that this removes an entire swathe of advisor costs, wouldn't they?

Readers interested in learning about the smoothed equity approach can read the award-winning paper to last year's international competition run by the UK's Institute and Faculty of Actuaries or my recent presentation to a TASC seminar

Auto-enrolment is on the agenda for IAPF's summer conference tomorrow. CEO Jerry Moriarty tells me that there are more pressing matters to discuss than my proposal for a smoothed equity approach to investment. How stupid of me to think that saving €1.4 billion a year was more important than deciding how best to offer workers a choice of investments.

I'm disappointed not to have the opportunity to explain how the smoothed equity approach delivers more than 50% better value than government's proposals, nor how it eliminates the risk of sharp falls in members' account values, to such an extent that AE accounts can be administered like high interest savings accounts. I'm also disappointed not be be able to explain how workers keep the same accounts post-retirement as they had pre-retirement, just drawing from them rather than adding to them. Surely, IAPF members would be delighted to learn that this removes an entire swathe of advisor costs, wouldn't they?

Readers interested in learning about the smoothed equity approach can read the award-winning paper to last year's international competition run by the UK's Institute and Faculty of Actuaries or my recent presentation to a TASC seminar